Apps are cool. Disruptively innovative. User-friendly. Buzzwords buzz. Tech companies are the good guys. Zuckerberg, Camp, Chesky, Musk and Bezos fly high, Marvel-like superheroes tossing marvels to the cheering crowds below. Media herald the benefits without critical analysis while the public lap it up without question.

Mission statements echo platitudes like connecting the world and don’t be evil while corporations disconnect the world and be evil.

Safety is thrown out the window in favor of hip convenience. 6000 sexual assaults are committed by Uber drivers in 2017 and 2018 alone. Property shortages caused by Airbnb block most millennials ever owning homes. Rents skyrocket, adding to poverty and homelessness while local governments scramble to regulate and keep their cities livable. Jeff Bezos is celebrated for being one of the world’s richest men, while Amazon staff work for a pittance in unenviable conditions; high streets are gutted and traffic congestion, pollution and carbon emissions proliferate. Social inadequate Mark Zuckerberg creates a purposely addictive unsocial platform which spreads fake news, constant outrage, polarized opinions, tribalism, groupthink, virtue signaling, and everything bad about people.

6000 sexual assaults are committed by Uber drivers in 2017 and 2018.

“Today we have access to highly advanced technologies. But our social and economic system has not kept up with our technological capabilities that could easily create a world of abundance, free of servitude and debt.”

Technology itself is neither good, nor bad. Rocket technology can be used to explore space and advance knowledge about our universe or deliver a nuclear payload to obliterate a city. Technology in the hands of greedy companies in a capitalist system will invariably be put to the task of making money for a few, at the expense of the greater human race. The vast array of modern technology today could be used to make human life better. To create integrated, pollution-free travel. To create vibrant community shopping districts selling local products. To ensure affordable housing for all.

It’s not.

Society is only just beginning to grapple with the social ills tech companies like Airbnb, Uber, and Amazon have unleashed.

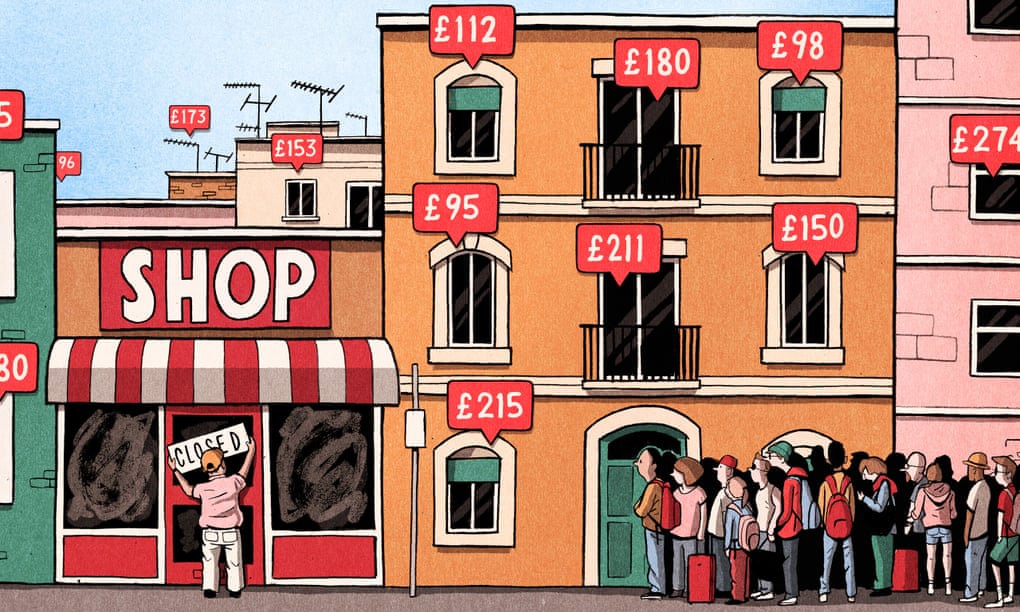

The city is for sale

Airbnb is Evil

Simone and Alice Cardillo arrive at their accommodation in Belfast to find it’s empty and for sale. They had booked and paid for the bogus property using the booking site, Airbnb.

As an example of how little Airbnb cares about you—the company only began vetting listings to see if they actually exist in 2019.

Let that sink in a moment.

Northern Ireland police chief superintendent Simon Walls says: “We know of people who’ve booked what they’ve thought are really good value weekends in good hotels and they’ve turned up to find there’s been no booking.”

There is one way to avoid being left out in the cold by scams. Book a Holiday Inn. The key benefit being, it will probably exist when you arrive.

Non-existent listings are, however, the tip of the iceberg.

Standing as the shining example of out-of-control technology making every day existence worse is Airbnb. Humanity has a tendency to embrace bad ideas, with the badness of the idea in direct correlation to humans’ excitement to get into it. Economic or political ideologies like Chicago School Economics or Islam... religions like Christianity or Scientology... Airbnb and the sharing economy. A bad idea so poorly thought through and ill-conceived, it makes the decision to install MCAS on the Boeing 737 Max seem positively inspired.

Scan a few news headlines:

“Airbnb and the so-called sharing economy is hollowing out our cities,” writes the Guardian.

“Six Brazilian tourists died Wednesday in downtown Santiago from a carbon monoxide leak in an apartment they rented through Airbnb,” echoes Bloomberg.

“Airbnb is getting blamed for Amsterdam’s housing crisis. So the city council is going to war against Airbnb,” says the New Statesman.

And these are not random, isolated problems, rather an integrated and essential part of the Airbnb business model.

Havoc wrought by Airbnb can be essentially grouped into four categories.

Short-term holiday rentals cannibalize long-term housing

- Destruction of urban communities

- Disruption for residents by unsavory short-term visitors

- Criminal behavior, scams, deaths and dangerous accommodation

These problems are largely driven by human greed: a profit-driven, unscrupulous company, greedy accommodation owners, and unthinking, gullible tourists sold into the idea that because it’s an app—it’s gotta be good for you.

A home is meant to be lived in and not a profit object.

Popular holiday islands, including Paros, are so overtaken by short-term rentals that some locals are being pushed out of their long-term home

1. Short-Term Holiday Rentals Cannibalize Long-Term Housing

Colette Nolan fell in love with the island of Paros 28 years ago when she moved there from the UK with her Greek now-ex-husband. “All my grandchildren were born and raised here,” the 60-year-old says. “I love being by the sea and the laid-back lifestyle.”

But Nolan’s time on the picturesque Cycladic island—famed for its blue-and-white painted houses—ran into a snag. Her landlord and landlady are asking her to leave the apartment she has lived in for five years so they can rent the property on Airbnb.

“They’re an elderly couple and they stay in the apartment above me for a month or two each summer,” she explains. “They told me they want my apartment back because they are struggling with the stairs. But when I suggested I move upstairs instead, they said their son wants to turn it into an Airbnb.”

Two-bed apartments like Nolan’s in her area of Paros average about €80 a night, versus Nolan’s €100 per month rent. That makes earning potential for landlords much higher, especially throughout the high season of June, July and August.

Short-term holiday rentals are causing housing shortages and rent increases in cities around the world. Problems like these are becoming common in areas where tourism is thriving: the number of short-term rentals eclipsing the number of homes where locals can live.

Renters Asked To Leave Homes Because Owners Want To Airbnb

On the other side of the country, on the Ionian island of Corfu, a similar situation is playing out. Corfu is larger than Paros—102,000 people live there all year round—the island also has a university.

Nikoleta Pandi, 30, says that she and her mother spent two years trying to find an apartment together before finally settling for a one-bedroom on the outskirts of Corfu Town. She sleeps in the bedroom and her mum in the living room.

“I was living in a village, but I wanted to be in Corfu Town for work,” she says. She found prices for two-bedroom apartments had jumped from less than €200 a month five years ago to €500 or more. “We pay €350 (for our one-bedroom), which is really cheap,” she says, adding that they found the apartment through a family friend, which is “the only way” for locals to find living arrangements now.

On other islands, anger at the situation is growing. Locals including George Tzimas, 28, says that students are hesitant to apply to local universities with the fear that they won’t be able to find any place to live.

Due to the prevalence of short-term holiday rentals students are being forced to live in hotels.

The irony is staggering.

Residents Forced Out Of Barcelona Neighborhoods

In Barcelona landlords have also realized they can make more money out of short lets to well-off Airbnb users than from renting to tenants who live and work in the city year round, so when contracts come up for renewal it’s not uncommon to find the rent shooting up to levels that young Spaniards can’t pay. Once they’re forced out of the neighborhood, the empty flat disappears into what’s known as the sharing economy although what happens next is the antithesis of sharing. Those lucky enough to own a desirable property get luckier, by pimping it out to the highest bidders. Meanwhile, those who don’t have such an asset become ever less likely to get one, as property prices are pushed up across the city. Thus inequality hardens, and resentment deepens, while the failure of government authorities to solve the problem drives the young and frustrated ever closer to the political fringes.

In response Barcelona has stopped issuing new tourism housing licenses, without which short-term rents are illegal. Barcelona council says short-term accommodation “creates speculation and illicit economies and its activities leave nothing positive for local neighbors, causing nuisance and complaints”.

Amsterdam To Block Vacation Rentals To Tackle Housing Shortage

Amsterdam is also changing its housing regulations to tackle the problems in the local housing market. Some main alterations proposed for 2020 include a quota on bed and breakfasts, banning holiday rentals in certain areas, giving young locals and healthcare and education staff priority for rental housing, and limiting room-based rentals to create more space for families.

The Red-Light District, Haarlemmerbuurt, and the Kinkerbuurt are among the first neighborhoods in the city where Airbnb and other vacation rentals could be banned. Other parts of the city may also face similar tight rules.

“In Amsterdam there is a dire shortage of homes. Many homes are now used as a profit object by tourist rentals or converted into rooms and rented out for maximum prices,” housing alderman Laurens Ivens says. “A home is meant to be lived in and not a profit object. This package of measures is needed to curb the craziness on the market and to keep Amsterdam livable for everyone.”

The city’s first goal is to prevent more living spaces rented through platforms like Airbnb, Booking or Expedia. From next year onward, all bed and breakfasts must apply for a permit from the municipality, and there will be a maximum number of permits for each neighborhood.

Another change is that from next year on, only the owner of a property can operate a B&B only if they live at that location. This is to prevent one owner operating many B&Bs in the city. The city is also changing regulations so that houseboats fall under the same rules as other homes. This means that from 2020, houseboat owners will also have to register with the municipality if they rent their homes out to tourists.

The municipality is also looking into whether vacation rentals are putting the quality of life under pressure in neighborhoods. The city will use the results of this study to decide whether a full ban on private holiday rentals is required.

The prevalence of short-term holiday rentals on the Greek university island of Corfu has led to students having to live in hotels

2. Destruction Of Urban Communities

Affordability aside, a rapid expansion of short-term lets alter an area’s atmosphere.

Sito Veracruz lives in the center of Amsterdam. “At first I thought it was a great idea,” he recalls. “But I now realize there are side-effects that we didn’t foresee. Airbnb can be a threat for cities.”

Veracruz, an urban planner, witnesses daily how the large number of apartments rented out on Airbnb and other short-stay rental websites are bringing more and more tourists to the central areas of Amsterdam. He says this has a negative effect on life in these neighborhoods—and he’s not only talking about the nuisance that noisy, partying tourists can create for the local residents.

“I think it’s obvious that Airbnb contributes to gentrification,” Veracruz says. “It drives up real estate prices that are already searing in Amsterdam. Neighborhood business that create ties between residents are replaced by businesses that only focus on tourists. Bike rental companies replace local grocery shops. And apartments that are continuously rented out to tourists are lost to people who want to actually live here.”

A study interviewed residents on the Hawaiian island of Oahu about their perceptions of short-term rentals. It identified both positive and negative effects—but more of the latter.

People were most worried about the sense of community being damaged. “This thing is changing the sense of place of the neighborhood. It’s changing the feel, with almost a revolving door of strangers,” one resident says.

Edinburgh’s heritage watchdog fears the character of the Old Town is being changed by short-term lets. “Short-term lets are having a terrible impact. They are hollowing out communities, both in the city center and across Edinburgh. Residents are putting up with high levels of anti-social behavior and, very worryingly for us, we believe there is a huge impact on housing supply,” says Councilor Kate Campbell (SNP), housing convener at City of Edinburgh Council. “Housing in Edinburgh is under enormous pressure and we need to take every action we can to protect supply and keep homes affordable for residents, as well as protecting communities.”

Isn’t This A Good Use Of Spare Rooms?

Many tourists applaud Airbnb for the opportunity to visit cities without paying large city hotel rates. Many homeowners join the chorus, saying the income from occasionally letting a spare room helps pay the bills. But almost half of listings come from hosts with over one property, and in London, 24% of listings are by hosts with five or more sites. It is a similar picture in Manchester and Bristol.

1% of hosts control 17% of the London’s Airbnb market.

In Bristol and Edinburgh, 1% of hosts are responsible for 11% of listings, and in Manchester it is 10%.

In London, there are 11 Airbnb hosts with over 100 listings each.

Eight of the 11 are listed with human-sounding host names, like “Sally”, offering 279 listings, “Veronica” (195), and “Emily” (179).

Airbnb argued that all three identified themselves as property managers. It says hosts may manage the listing process on behalf of several different individuals.

What's clear is this is not a homeowner earning some extra pocket money to pay the bills: it’s an industrial scale property-rental business.

In Brighton and Hove, there are about 17,000 people waiting for housing. In 2016, 60 % of the nearly 3,000 Airbnb listings in the city were entire homes—that’s a huge number of properties which could have been used to house people who desperately need a secure roof over their head.

The link between Airbnb, rising rents and homelessness is not debatable. “We have a massive homelessness crisis, we’re coming up on 70,000 homeless people in the city, and we have thousands of apartments listed essentially as hotel rooms,” said Jonathan Westin, executive director of housing rights group New York Communities for Change.

An affordable, secure home is a basic human right. When there is a desperate shortage of housing it cannot be right that homes are being turned into rooms for tourists.

Short-term lets add to problems of over-tourism. Barcelona and Venice, for example, each receive over 30 million visitors a year, leading to vigorous debate about the consequences. Prague receives 8 million tourists each year. Prague 1 and 2 are filled with shops catering to the tourist trade with cheap junk; few stores exist selling essential goods for residents, altering the rustic, creative atmosphere of a city to little more than a Disney theme park.

3. Disruption For Residents By Unsavory Short-term Visitors

Examples of anti-social behavior in party flats have been well highlighted by review site Airbnb Hell and campaigners for greater regulation; late-night/early-morning noise, couples having sex in common areas, threatening children, unknown vehicles parking in driveways. As a resident what can you do? Try complaining to the police or to Airbnb? As one neighbor affected by an Airbnb rental said: "It’s not like we were expecting much, but Airbnb somehow exceeded our expectations in not giving a single f#$k about us or our complaints. The police–I was told the last time I called–are generally putting up with too high a volume of calls to deal with noise complaints."

Then there’s Airbnb apartments rented out to shoot porn. Michael Lucas, an adult performer and producer, and owner of Lucas Entertainment says he’s worked in adult film nearly 20 years, and using Airbnb for porn locations is common. “We rent houses all the time,” he says.

Councils say it is expensive and time-consuming to tackle such problems with their existing powers. Living next door, or down the hall from an Airbnb is likely to be like having a revolving door of neighbors from hell. And there’s little residents can do.

Neighborhood business that create ties between residents are replaced by businesses that only focus on tourists. Bike rental companies replace local grocery shops. And apartments that are continuously rented out to tourists are lost to people who want to actually live here.

Change and souvenirs. Literally no useful shops for locals in Prague 1

4. Criminal Behavior, Scams, Deaths And Dangerous Accommodation

On October 31, 2019, five young people died in a mass shooting during a 100-plus person house party at an Airbnb rental in the San Francisco Bay Area town of Orinda, California.

The family of slain 23-year-old Raymon Hill Jr. says they’re suing Airbnb for allegedly not vetting its listings and the people who rent homes through the platform.

“Airbnb only decided to change any of their policies when they saw public opinion turning against them after multiple lives were lost,” Jesse Danoff, an attorney representing the Hill family, says in a statement. “There was ample knowledge and ample time to know this could and should have been done long before.”

Shootings at Airbnb rentals aren’t rare. They happen regularly. In the past six months, at least 42 people have been shot at short-term rentals in the US and 17 people have died, according to a report by the San Francisco Chronicle.

Airbnb CEO and cofounder Brian Chesky tweeted that the company would ban “party houses”.

But a simple search of the term “Party House” in December 2019, over a month after his pledge still pulls up plenty of listings like: PARTY HOUSE CLOSE THE CITY CENTER Family house for max 16 people.

There are also serious questions around issues such as compliance with fire safety regulations, for example. Not only does this put tourists at risk, it also poses unfair competition with those registered guest houses and bed and breakfasts that are required to meet higher standards.

Airbnb Host Kills Guest Who Couldn’t Afford Bill

In May 2019 an Australian jury convicted Jason Colton, 42, of the 2017 killing of Ramis Jonuzi.

A court heard two housemates had held the 36-year-old down, while Colton beat and strangled him for not paying the A$210 (£113, $149) he owed.

Mr Jonuzi, a 36-year-old bricklayer, had packed his bags and was about to leave the home when he was attacked.

Justice Elizabeth Hollingworth says Colton instigated the violence. “You lunged at him, grabbed him by the collar, spun him around, and threw him against the wall,” says the judge.

Don’t pay your bill at the Hilton and chances are police will be called. Jail or a fine could result. The concierge will probably not beat you to death.

Always a positive factor when booking holiday accommodation.

Few-To-No Background Checks

It’s not only guests in danger. Inviting strangers into your home is wrought with risk. Yet hosts seem willing to take it daily. In 2018, an Airbnb guest who was staying in the spare room of a family home pleaded guilty to attempting to sexually assaulting the homeowner’s seven-year-old daughter.

According to police, the Airbnb host had rented out the room to 28-year-old Michigan man Derrick Kinchen.

The host says he found Kinchen lying naked next to his daughter in her bedroom while her nightgown had been pulled up. The father made the horrifying discovery shortly after midnight after noticing the lights on in the house.

Another Airbnb guest filed an ongoing lawsuit against the company in 2017, saying it failed to do a background check that would have uncovered the previous arrest of a host who she says sexually assaulted her.

In July 2016, Ms. Lapayowker rented a studio apartment in Los Angeles that was attached to the home of Carlos Del Olmo, listed as a superhost because of his positive reviews on the site. Though she rented the property for a month, the suit says she had stayed only three nights because Mr. Del Olmo’s behavior—which included making sexually suggestive comments, and using drugs in front of his underage son—made her uncomfortable.

According to the suit, the assault occurred when she returned a week after leaving the studio, to retrieve belongings she had left behind. Mr. Del Olmo told her he wanted to show her something important inside the studio and locked the door after she followed him in. She was held in a chair, against her will, as he masturbated in front of her, finally ejaculating into a trash can, the lawsuit says.

The suit arrives while Airbnb is touting on-the-ground hosts who guide guests through customized itineraries, bringing host and guest into increasing risky contact with one another. It also lays bare Airbnb’s poor track recording of background checks on hosts and guests, and inability to ensure people’s safety in such a business model.

Leslie Lapayowker contends that a background check would have uncovered the fact that the owner had been arrested and charged with battery and prevented him from listing property on Airbnb.

Before she fled the scene, the suit charges, the host says to her, “Don’t forget to leave me a positive review on Airbnb.”

Ban Airbnb (And Other Sharing Economy Sites) Everywhere

Airbnb aims to host one billion guests each year by 2028.

Like all companies, Airbnb is driven by one thing: growth and maximizing profit for shareholders—with scant regard for the social consequences.

A 2019 Economic Policy Report found:

- The economic costs Airbnb imposes likely outweigh the benefits.

- Airbnb might, as claimed, suppress the growth of travel accommodation costs, but these costs are not a first-order problem for American families.

- Rising housing costs are a key problem for American families, and evidence suggests that Airbnb raises local housing costs.

Essentially, the one positive of Airbnb is marginally reduced holiday costs—predominantly of interest to white middle classes. The rich don’t care, and the poor are too busy spending on essentials like ever increasing rent to worry about holidays. And even among this small group who benefit—holiday accommodation price isn’t high on their list of priorities.

Which begs the question, why does Airbnb exist?

Cities around the world are grappling with ways to regulate Airbnb. Still half of the Amsterdam flats on Airbnb are rented out over 60 days a year. A quarter of the hosts have multiple listings—with some identified as more likely to be running a commercial business. Enforcement of these rules involves a high financial cost for councils and governments, ultimately to taxpayers, and is next to impossible.

There’s no regulating or taming such a monstrosity.

The only solution is for cities must ban the house sharing business model in its entirety.

There’s a deeper discussion over home ownership. The way to address rising rents, housing shortage and homelessness may be simple—to ban the sale of homes for investment. To make it illegal to own homes over and above the one you live. This would free up accommodation for those who need it at affordable prices, but are citizens willing to sacrifice personal greed in return for a better society?

Every time you stay in an Airbnb you’re supporting continued damage to the social fabric of the place you’re visiting, and hurting your own renting and future home ownership prospects back home.

Just as Socrates foretold, people can be coerced into voting against their best interests, so too consumers are being coerced into making purchases and supporting companies which impact their own interests, negatively.

For those about to take an Instagramable photo of their cool Airbnb apartment, ask first: do you want to be a good, socially-aware citizen, or do you not care what you support?

Here’s an innovative idea.

Here’s a disruptive, innovative idea.

A business runs an establishment with professional, paid staff, on-site security, providing accommodation, meals, and other services for travelers and tourists in a specific-for-use building in a location zoned for business. They don’t cause a rise in accommodation prices. They don’t hollow out vibrant communities. They don’t beat guests to death.

I call it a hotel.

Airbnb: Damage to Society Rating 9/10

The economic costs Airbnb imposes likely outweigh the benefits. Airbnb might, as claimed, suppress the growth of travel accommodation costs, but these costs are not a first-order problem for American families.

Worldwide Short-term Rental Restrictions

- Amsterdam: Entire home rentals limited to 60 days a year, set to be halved

- Barcelona: Short-term rentals must be licensed but no new licenses are being issued

- Berlin: Landlords need a permit to rent 50% or more of their main residence for a short period

- London: Short-term rentals for whole homes limited to 90 days a year

- Palma: Mayor has announced a ban on short-term flat rentals

- New York City: Usually illegal for flats to be rented for 30 consecutive days or fewer, unless the host is present

- Paris: Short-term rentals limited to 120 days a year

- San Francisco: Hosts must obtain business registration and short-term rental certificates. Entire property rentals limited to 90 days a year

- Singapore: Minimum rental period of six consecutive months for public housing

- Tokyo: Home sharing legalized in only 2017. Capped at 180 days per year